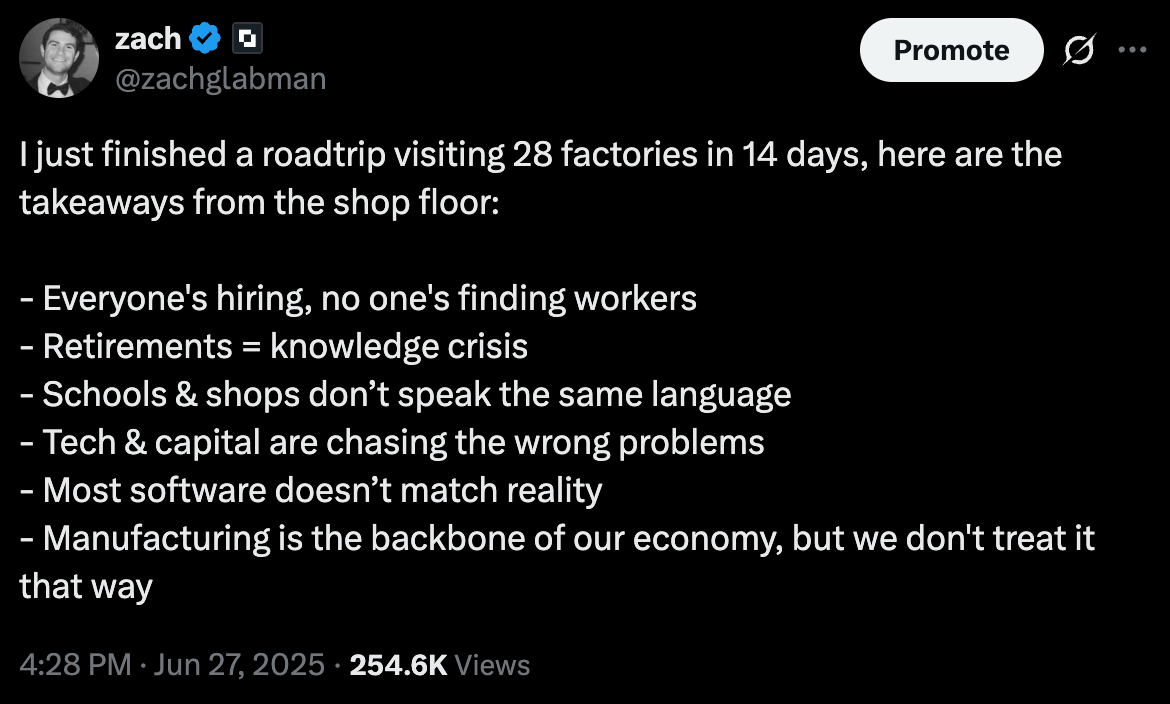

I just spent 14 days visiting 28 factories across America—from machine shops in Detroit to aerospace suppliers in Los Angeles. What I found wasn’t industrial decline, but something unexpected: a $2.5 trillion manufacturing sector stuck in gridlock, sitting on the cusp of a renaissance that could redefine the American economy.

Why Making Things Still Matters

America’s economic security depends on making things, not designing them. The current narrative says globalization lets us do the “high-value” work while outsourcing production. After all, why do the gritty work if another country with cheaper labor can take care of it?

That kind of short-term thinking drives long-term innovation away.

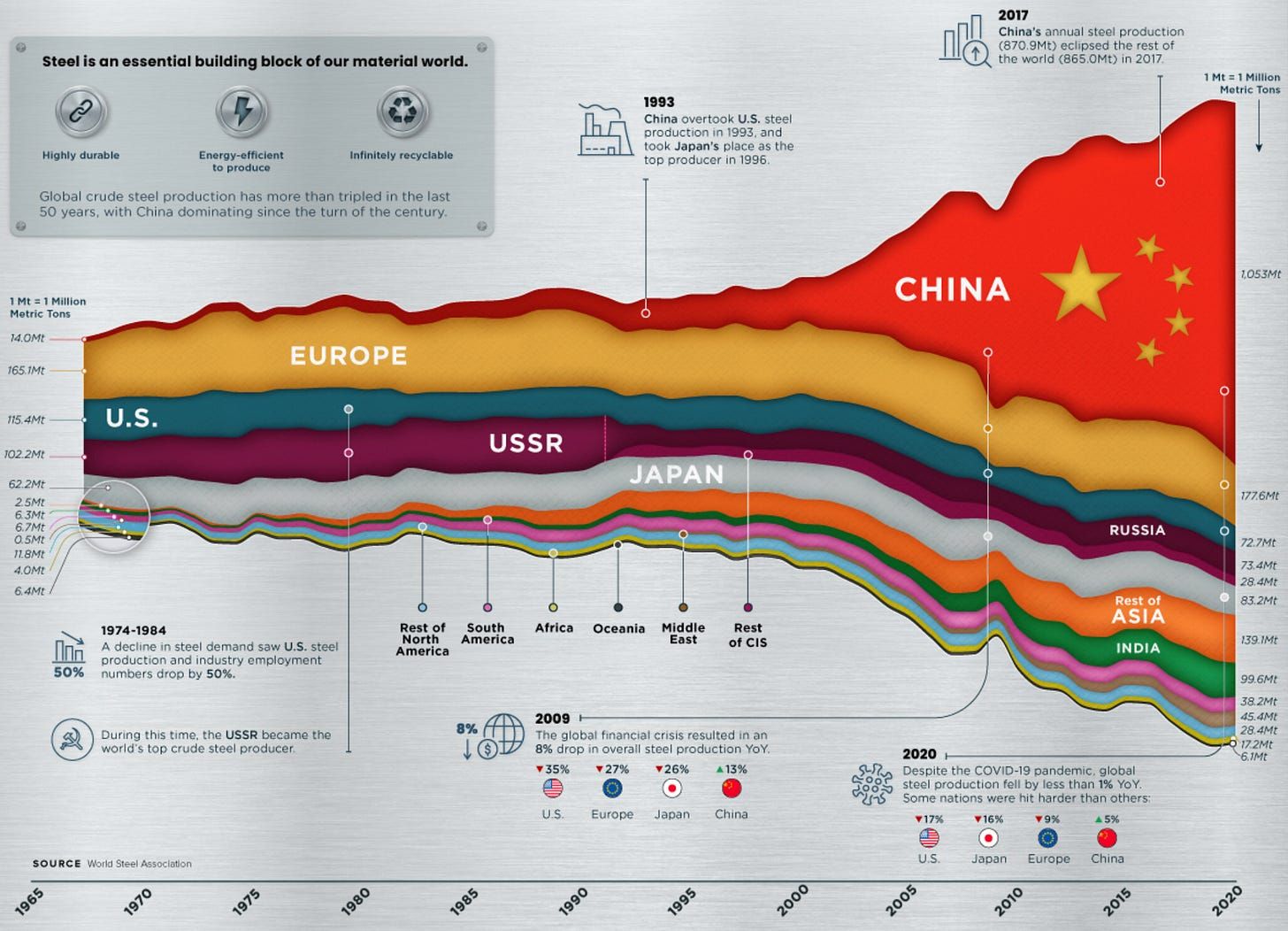

In 1953, manufacturing employed one in three American workers and generated 28% of GDP. Today both figures have collapsed to under 10%. In 1944 at peak wartime steel production, we made around 80 million tons of steel annually. We still make that much today. But that 80 million tons was 60% of global production in 1944. Today it’s just 4%. Now we import around 30 million tons a year.

The world scaled up around us while we scaled down

Production capability is inseparable from innovation capability. When you design, change, and manufacture a part, there’s a continuous feedback loop between engineering and production that drives innovation. Break that loop by separating design from manufacturing, and over time you lose efficiency . Eventually, you lose the ability to invent the next generation of products entirely.

The Great Offshoring: How We Lost More Than Jobs

Innovation Follows Production (Whether We Like It or Not)

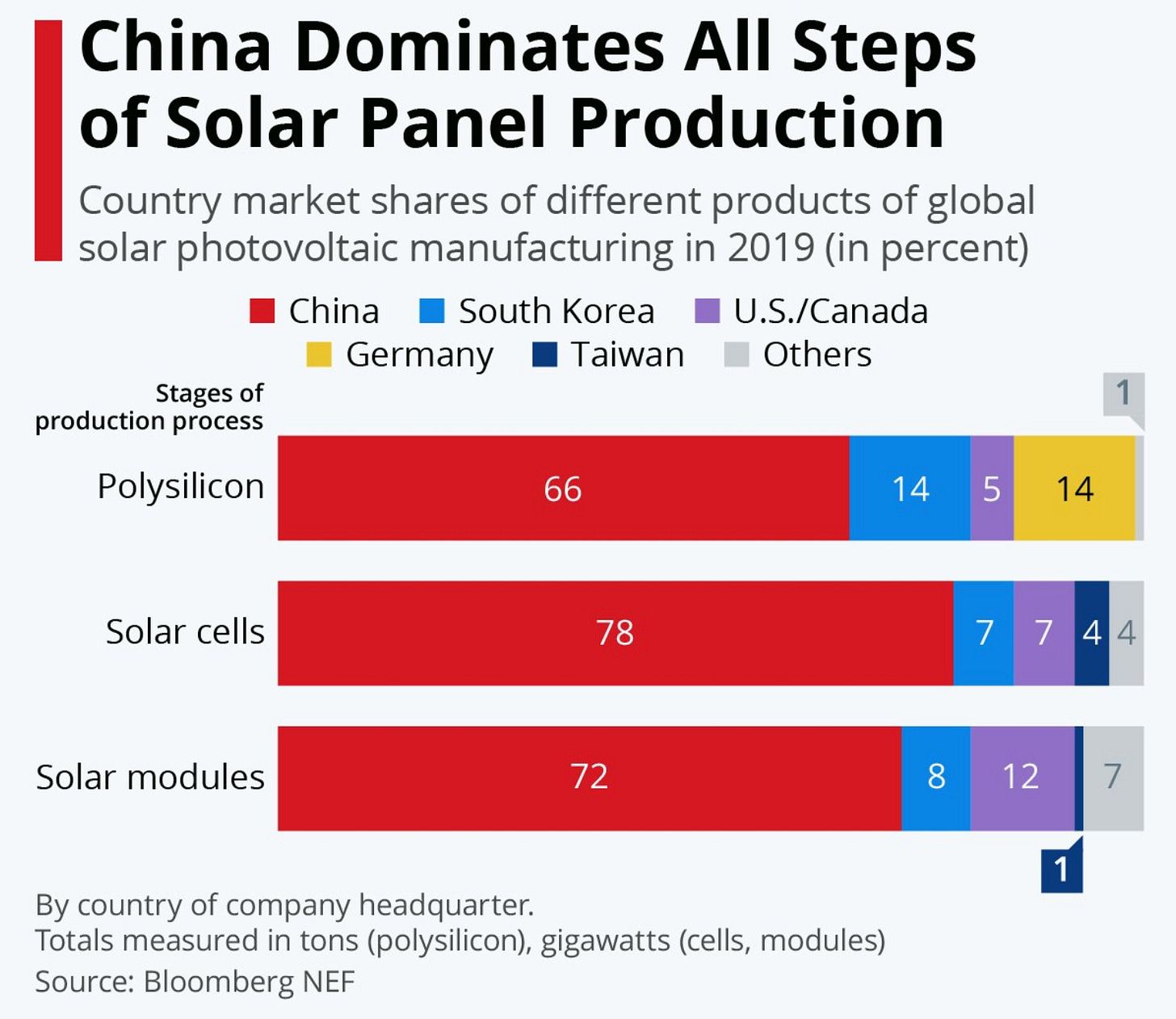

Take solar panels. America invented photovoltaic technology at Bell Labs. We led early commercialization. But when production moved to China for cost reasons, process innovation followed.

In the beginning, Chinese manufacturers made American-designed panels cheaper. Then they redesigned the entire manufacturing process to make better panels. Today, China holds most of the key patents in solar manufacturing and produces over 80% of global panels.

They’re crushing electrification and power generation.

When you manufacture something, you learn how to make it better. Every production run reveals process improvements, design tweaks, material behaviors. That information doesn’t travel well. When design and manufacturing are far apart, iteration slows and quality suffers.

Intel co-founder Andy Grove saw this coming : “Without scaling, we don’t just lose jobs—we lose our hold on new technologies.” He was right. Lose the ability to scale, and you eventually lose the capacity to innovate.

The Knowledge That Walks Out the Door

Manufacturing knowledge isn’t something you learn from a textbook alone. It’s instinct built through years of experience. How do you troubleshoot when a process goes wrong? What does good quality look, sound, and feel like?

Right now, there are 80-year-olds working on shop floors with priceless tribal knowledge living in their heads. We’re 5-10 years away (maybe closer) from the largest knowledge and wealth transfer in industrial history. When production moved overseas, much of this institutionalized expertise went with it. American companies found themselves dependent on foreign suppliers for lower costs, and inevitably for manufacturing capabilities they no longer possessed.

And many groups have tried to fix it! Government has talked about manufacturing jobs in some way shape or form in every election cycle since the industrial revolution. Following WWII, China got us hooked on their manufacturing the way Britain got them hooked on opium. We told ourselves we could bring manufacturing back whenever we wanted. Turns out it’s not that easy.

Supply Chain Dependency

COVID showed us what happens when you can't make things yourself.

China controls vast chunks of global supply chains—not by accident, but by design. While we optimized for quarterly profits and election cycles, China built manufacturing capacity as a decades-long strategic priority. Today they produce roughly 30% of the world's manufactured goods and are deeply wired into US supply networks. "Made in America" doesn't mean much when Beijing controls the raw materials we need for everything from EVs to missiles.

The geographic concentration is alarming: over 80% of global semiconductor manufacturing is concentrated in the Indo-Pacific , with Taiwan's TSMC alone controlling most advanced chip production. In a conflict scenario, loss of access would cripple everything from consumer electronics to defense systems. We depend on an East Asian manufacturing hub that is itself under threat.

We can’t quit cheap outsourced production because we’ve lost the muscle memory to make things ourselves. During COVID, we discovered that 95% of our ibuprofen and 40% of our penicillin came from China . 99% of our nitrile gloves still come from China. If they raised prices by 50% tomorrow, we’d have a medical crisis on our hands (literally..no gloves).

Recent policy has tried to address the most critical manufacturing. The $52.7 billion CHIPS Act . The $375 billion Inflation Reduction Act . But implementation is messy: TSMC’s Arizona chip fab is hitting delays because we don’t have enough skilled workers to staff it. Turns out rebuilding supply chains is harder than cutting checks.

What I Actually Found on the Shop Floor

Visiting 28 factories showed me that doomer narratives are dead wrong: American manufacturing isn’t dying. It’s evolving. Most people still think manufacturing is dirty, dangerous work from the 1970s. But these aren’t your grandfather’s factories.

“We have a reputation problem. Manufacturing jobs are a tough sell. We need to find a way to show people that we’re not some dirty, dangerous facility like you see in the movies. Our plant is clean, safe, largely automated and looking for people to help us grow.” -Plant Manager

I documented the whole journey on X

Hiring

A handful of shops have turned down orders because they can’t find people. But the jobs are good. Walking the floor at a joint manufacturer in Illinois, it was immediately clear that employees work in great conditions: tons of natural light on an air conditioned floor. They can make six figures without a college degree, work with robots and are encouraged to solve problems creatively and grow at the company.

Knowledge Transfer

Sixty-year veterans with irreplaceable expertise are retiring faster than we can transfer their knowledge. Dan Sutterlin at Sutterlin Machine in Mentor, Ohio introduced me to a few of his silver-haired machinists who know more about metallurgy and mechanical process than most engineers. He’s actively working to make sure that when they retire, all their knowledge doesn’t go with them.

Tech Gap

“We need systems that work for our business”

I heard this 20+ times. These shops run on legacy ERPs from the 1980s, failed SAP implementations, and Excel spreadsheets. Some are fully on paper! A $20M aerospace supplier showed me their scheduling system: a whiteboard with color-coded magnets. “We tried three software solutions,” the owner said. “They all sucked. This works better.” This is what we're building at DOSS.

Capital Desert

Manufacturing companies face a mismatch between the capital they need and what's available. Profitable $8M companies can't get growth capital because the returns don't match what investors expect in their typical timeframes. VC and PE models don't work for manufacturing—these businesses need patient capital that can hang on for 10-20 year horizons, not capital looking for a 3-year exit. The financing gap is real and measurable: even profitable shops can't grow because traditional lending requirements are misaligned with manufacturing realities. In Cleveland, I met owners who need three years of positive EBITDA just to qualify for loans, despite having steady revenue and order backlogs. Meanwhile, they're turning down orders because they lack the capacity to fulfill them.

It’s ironic—capital exists, but it's not flowing to businesses that actually make things. Tesla's near-collapse in 2017-2018 during the Model 3 production ramp showed how even well-funded companies struggle when manufacturing complexity requires a lot of upfront liquidity. If Tesla, with access to public markets and Elon's celebrity, nearly failed at scaling production, imagine the challenge for smaller manufacturers trying to grow with traditional financing.

The $2.5 Trillion Gridlock Problem

American manufacturing has all the pieces for a comeback, but the stakeholders can’t get their act together. Industry, education, government, and tech all want the same thing but lack the incentives to work together.

Industry vs. Education

U.S. manufacturers can’t find enough skilled workers even though millions of Americans need decent jobs. There are 900,000 open manufacturing jobs right now, expected to hit 2.1 million unfilled positions by 2030 .

The workforce exists, they just don’t have the right skills. For decades, American education abandoned vocational training. High schools killed shop classes. Society pushed the idea that four-year degrees are the only path to success. Meanwhile, manufacturing went high-tech and all the skilled baby boomers started retiring.

Visiting Lucas Pacheco at Hawthorne High’s Machine Shop

We produce plenty of liberal arts graduates but nowhere near enough CNC machinists, robotics technicians, or welders. As one report put it: the manufacturing industry doesn’t lack opportunity, it lacks alignment between skills taught and skills needed.

Government vs. Industry

Washington has been paranoid about manufacturing for years. Trade policy delivered cheaper goods but destroyed manufacturing communities. Only recently has DC pivoted to having some semblance of industrial strategy.

Even now, the left hand doesn’t know what the right hand is doing. We impose tariffs to protect industries but don’t invest in workforce development. We subsidize new chip fabs but can’t staff them because we don’t have enough skilled workers. This is what happens when industrial policy comes purely from lobbyists and boardrooms rather than walking on shop floors.

Tech vs. Manufacturing

For the last 20 years, America’s innovation energy and capital was wasted on 15-minute grocery delivery and dating apps—all while the US still doesn’t have a single mile of high speed rail. Hardware and industrial innovation have been starved for capital and attention for too long.

The mentality was that America would do the “innovating” while other countries did the “commodity” work. Steve Jobs captured this perfectly in 2011 when Obama asked why Apple couldn't build iPhones in America: “Those jobs aren't coming back.”

That attitude became self-fulfilling. The more production expertise migrated abroad, the harder it became to bring it back. And now Apple is stuck in China.

The Defense Trap

Every machine shop I visited told the same story. Commercial manufacturing gets crushed by overseas competition, so the only profitable path left is chasing aerospace and defense work that China can’t legally touch due to ITAR restrictions. New $150B investment into defense and military technology doesn’t quite incentivize people to invest elsewhere, either.

This creates a vicious cycle. Capable shops compete for the same defense contracts while broader US manufacturing dies. It’s “manufacturing purgatory”—surviving but not thriving. We end up with a manufacturing sector that's increasingly dependent on military spending rather than building the diverse industrial capacity we need for long-term economic strength.

Why Now Is Different

A few trends are finally aligning to make American manufacturing competitive again:

Technology: Automation has collapsed the labor-cost gap. China ranked 3rd globally for robot density in manufacturing in 2023, while the US ranked 10th . But there are automation-first factories popping up everywhere in the US: Hadrian vertically-integrating aerospace/defense part production, SendCutSend for sheet metal, Forge Automation for machined parts, Senra Systems for wire harness.

Economics: Chinese manufacturing wages have risen 400% since 2000 . The 2021 chip shortage cut U.S. GDP by $240 billion. Supply chain risks now carry measurable costs.

Geopolitics: Strategic competition makes supply chain independence a national security issue . Unclear with rising tensions in Eastern Europe, the Middle East, South America and East Asia what the future of “globalization” actually looks like.

Workforce: It’s not a popular or glamorous thing to become a manufacturer, machinist, welder or CAM programmer. Students are pushed toward college despite clear career security (and lack of debt) by going into this line of work.

But these trends only matter if we can connect them. Each piece of the puzzle depends on another piece existing for it to fit somewhere.

The Coordination Imperative

The manufacturing skills gap could cost the U.S. economy $1 trillion by 2030 . Every stakeholder group needs to get on the same page:

- Industry + Education: 89% of executives report talent shortages while millions need jobs. Use this frustration as fuel to fix the pipeline problem. Align training with actual shop floor needs. Fund apprenticeships like we fund internships. Build localized pipelines that create real job mobility.

- Government: Sweeping policies ( tariffs for example ) don’t work by themselves. Make trade policy, education, and infrastructure work together instead of against each other with complementary policies to invest in industry and job creation .

- Tech + Manufacturing: The disconnect is destructive. Tech chased lifestyle software while production was pushed out overseas. Manufacturing is tech now, time to walk the shop floor and figure out what’s missing!

- Capital: Durable industries need durable, patient capital. Stop rewarding quarterly thinking over long-term building for critical industries

When these groups actually work together, good things happen. The CHIPS Act is a test case: Commerce grants, companies like TSMC, state governments, local colleges all coordinating. If it works, it’s a model to apply to other industries.

Coordination in action

Some of the most successful manufacturers I visited have solved some of these problems through employee stock ownership plans (ESOPs). When workers own equity in the company, they think like owners - embracing automation and efficiency improvements because they share in the upside. There are roughly 6350 companies in the US that opt for this model!

Believe it or not, I met a company doing $250M topline with close to 60% gross profit margin. ESOP. They’ve never laid anyone off (+insane retention), are growing like a tech company and actively exploring new avenues for growth. Sounds like a story out of Silicon Valley.

Other interesting models: Companies like Protolabs and Fictiv create networks of smaller manufacturers, giving them access to bigger contracts while providing customers with distributed capacity. Siemens runs apprenticeship programs that partner directly with community colleges to train students on the exact equipment and processes they'll use on the job.

The Choice We’re Making

This isn’t about choosing high-tech services or manufacturing. Modern manufacturing is high-tech. It’s robotics-enabled production, AI-enhanced operations, materials science breakthroughs and hybrid programmer-operators.

Standing by the reactor with Isaiah at Valar Atomics

Manufacturing is how we solve climate change (energy tech, weather modification tech , etc), create good jobs across skill levels, and stay competitive globally. The renaissance will happen when we realize that making things is how you learn to make better things. Innovation happens where design meets production. Economic security comes from being able to produce what you need.

America has world-class companies, top universities, tons of capital, and creative entrepreneurs. We don’t lack the capability.. we’ve been making some damn good stuff for 100+ years. We lack coordination to modernize and develop our infrastructure.

The $2.5 trillion manufacturing sector is waiting for alignment.

We have maybe 5-10 years before this window closes. Other countries are racing to reinforce their manufacturing advantages and build the world's most advanced industrial base.

The factories are ready. The workers are eager. The technology exists and is itching to be used on the floor. The only question is whether we’ll get our act together in time to lead the next industrial revolution, or watch others build it while we’re still arguing.